Article seen originally in The New York Times / Opinion

In the near future, the story of drugs like Ozempic may no longer be primarily about weight loss and diabetes. We now know that these drugs can reduce heart and kidney disease. They could very well slow the progression of dementia. They might help women struggling with infertility to get pregnant. They are even tied to lower mortality from Covid.

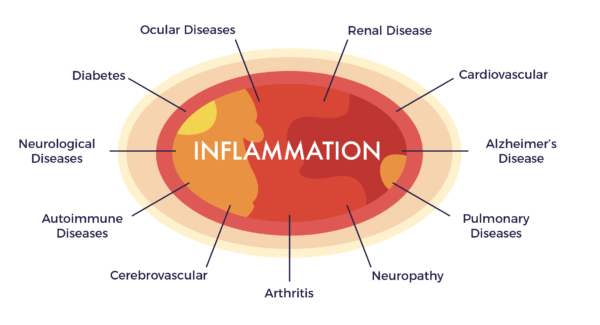

It’s easy to attribute this to the dramatic weight loss provided by Ozempic and other drugs in its class, known as GLP-1 receptor agonists. But that isn’t the whole story. Rather, the drugs’ numerous benefits are pointing to an emerging cause of so much human disease: inflammation.

As a critical care doctor, I have long considered inflammation a necessary evil, the mechanism through which our bodies sound an alarm and protect us from threat. But a growing body of research complicates that understanding. Inflammation is not just a marker of underlying disease but also a driver of it. The more medicine learns about inflammation, the more we are learning about heart disease and memory loss. This should serve as a reminder of the delicate balance that exists in our bodies, of the fact that the same system that protects us can also cause harm.

Inflammation is the body’s response to infection or injury. Our innate immune system — the body’s first line of defense against bacterial or viral intruders — protects us by triggering an inflammatory response, a surge of proteins and hormones that fight infection and promote healing. Without that response, we would die of infectious disease in childhood.

But by the time we make it to our 50s and beyond, our innate immune system can become more of a hindrance as inflammation begins to take a toll on the body. Acute inflammation, which happens in response to an illness, for instance, is often something we can see — an infected joint is swollen and red. But chronic inflammation is usually silent. Like high blood pressure, it’s an invisible foe.

To understand what inflammation reveals about a person’s health, it’s important to know what’s causing it. Sometimes inflammation is the body’s reaction to something else — smoking, for instance, or obesity. Chronic inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, result in high levels of inflammatory markers in the blood. Viral infections like Covid also lead to inflammation, particularly in long Covid. But there is also what Paul Ridker, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, calls “low-grade silent inflammation,” inflammation that is not clearly secondary to any underlying disease but is the consequence of the immune systems that keep us alive.

“No one feels this inflammation, the same way no one feels their cholesterol or blood pressure,” he said. But it matters.

Dr. Ridker is one of the scientists credited with building a new understanding of inflammation, specifically how it can lead to heart disease. In the mid-1990s, he noticed many of his patients had suffered strokes and heart attacks despite having normal levels of cholesterol — which was thought to be the primary cause of heart disease. He and his colleagues also noticed these patients had elevated markers of inflammation in their blood, and he began to wonder if the inflammation wasn’t a side effect but actually came first.

To parse out cause and effect, chicken and egg, Dr. Ridker and his team analyzed blood samples from healthy men who had agreed to be tracked over time. Their findings “changed the whole game,” Dr. Ridker said. Seemingly healthy people with elevated levels of inflammation went on to have heart attacks and strokes at much higher rates than their less inflamed counterparts. The inflammation indeed came first, meaning it wasn’t only a consequence of heart disease but also a risk factor for developing it, such as high blood pressure or cholesterol.

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic may tell a similar story. They also appear to lower heart disease deaths among people taking them who lose a huge percentage of their weight and those who lose significantly less.

Daniel Drucker, an obesity researcher at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto who was involved in the discovery of the new drugs, has received letters from people taking drugs for obesity who suddenly discovered that their painful rheumatoid arthritis is in remission, swelling and pain gone after years of suffering despite appropriate medication. These examples don’t prove that decreasing inflammation is the reason, but it’s a leading theory, Dr. Drucker told me.

There’s also increasing evidence that inflammation affects dementia and, more broadly, aging itself. Our cells have pathways that they use to regenerate and repair themselves, and inflammation activates programs in the cells and tissues that take away that ability. Perhaps, some scientists wonder, if inflammation accelerates aging, drugs that can tamp down inflammation, including GLP-1s, can slow cognitive decline and shift the course of aging.

But currently there is no public health recommendation in the United States for primary care practitioners to measure markers of inflammation in all adults. Perhaps that will change. New research from Dr. Ridker and his team shows that a one-time measurement of a particular marker of inflammation may help predict the rate of stroke, heart attack and death from heart disease in women over the coming decades.

With all this, it’s tempting to want to stamp out inflammation entirely. But that would not come without harm. The pathways involved in inflammation remain necessary to ward off infection. That’s why patients with inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus who take immunosuppressive drugs are predisposed to infection. There is a complicated balancing act here. Inflammation worsens outcomes independent of the underlying medical condition that causes it. And yet, if one were to wipe out the immune system, we wouldn’t be inflamed but we would die from sepsis.

We saw this at the bedsides of Covid-19 patients. It was clear early in treatment that the damage the virus wrought was because of both the virus itself and the body’s powerful inflammatory response. As a result, in those desperate early months of the pandemic, without a robust body of evidence to guide us, we treated patients with high-dose steroids and potent medications aimed at suppressing the immune system. This worked by some metrics (and we still use steroids in some cases). The markers of inflammation fell. Fevers subsided and blood pressure stabilized. But anecdotally, we also saw bacterial infections flourish. I remember one patient treated with immune suppression and high-dose steroids for weeks upon weeks who ultimately survived Covid but died of a rare fungal infection, a consequence of immune suppression.

As with so much in medicine, the mechanism the body needs to stay healthy is the very same mechanism that can harm us. With our increasing knowledge of inflammation will come new treatments, new methods of monitoring, new understanding — but we will not rid ourselves of inflammation entirely. We wouldn’t want to. There is always a cost.