Original article found at VitalChoice.com

Food makers cracked the “hyperpalatability” code and it’s fattening us; Brain’s impulsivity circuit revealed in separate study

Why it can be hard to stop eating even when you’re full: Some foods may be designed that way

By Tera Fazzino, Ph.D., and Kaitlyn Rohde, B.S.

All foods are not created equal.

Most are palatable — that is, tasty to eat — because we need to eat to survive. For example, a fresh apple is palatable to most people and provides vital nutrients and calories.

But foods like pizza, potato chips, and chocolate chip cookies, are almost irresistible. They’re always in demand at parties, and all too easy to keep eating even when we are full.

In these foods, a synergy between key ingredients can create an artificially enhanced palatability experience that’s greater than any one ingredient would produce alone. Researchers call this hyperpalatability. Eaters call it delicious.

Initial studies suggest that foods with two or more key ingredients linked to palatability — specifically, sugar, salt, fat or carbohydrates — can activate brain-reward neurocircuits in ways similar to addictive drugs such as cocaine or opioids. They may also be able to bypass mechanisms in our bodies that make us feel full and tell us to stop eating.

Our research focuses on rewarding foods, addictive behaviors and obesity. We recently published a study with a University of Kansas colleague — nutritional scientist Debra Sullivan, Ph.D., R.D. — that identifies three clusters of ingredient combinations that can make foods hyperpalatable (Fazzino TL et al. 2019).

Using those definitions, we estimated that nearly two-thirds of foods widely consumed in the U.S. fall into at least one of those three groups of hyperpalatable foods.

Cracking the addictive-food code

Foods that are highly rewarding, easily accessible and cheap are everywhere in our society. Unsurprisingly, eating them is associated with obesity.

Documentaries released over the last 15-20 years revealed that food companies have figured out how to make foods especially enticing. But they typically treat their recipes as trade secrets, so academic scientists can’t study them.

Instead, researchers have used descriptive definitions to capture what makes some foods hyperpalatable.

For example, in his 2012 book, Your Food Is Fooling You: How Your Brain Is Hijacked by Sugar, Fat, and Salt, David Kessler, former Commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), wrote, “What are these foods? Some are sweetened drinks, chips, cookies, candy, and other snack foods. Then, of course, there are fast food meals — fried chicken, pizza, burgers, and fries.”

But there is no agreed definition of hyperpalatable foods, making it hard to compare results across studies, which often fail to identify the relevant ingredients.

So, we conducted our study in an attempt to establish a quantitative definition of hyperpalatable foods and use it to determine how prevalent these foods are in the U.S.

Hyperpalatable foods fall into three clusters

We conducted our work in phases. First, we searched the biomedical literature to identify scientific papers that used descriptive definitions of the full range of palatable foods.

We then entered those foods into standardized nutrition software to obtain detailed data on the nutrients they contained.

Next, we used a graphing procedure to determine whether certain foods appeared to cluster together, and found that hyperpalatable foods fell into three distinct clusters:

- Fat and sodium: More than 25% of total calories from fat, consisting of at least 0.30% sodium by weight. Bacon and pizza are examples.

- Fat and simple sugars: More than 20% of total calories from fat and more than 20% of total calories from simple sugars. Cake is an example.

- Carbohydrates and sodium: More than 40% of total calories from carbohydrates (i.e., sugars and starches), consisting of at least 0.20% sodium by weight. Buttered popcorn is an example.

Then we applied our definition to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, or FNDDS, which catalogs foods that Americans report eating in a biennial federal survey on nutrition and health.

The USDA database contained 7,757 food items, and more than 60% met our criteria for hyperpalatability. Fewer than 10% of foods fell into multiple clusters.

- 70% — including many processed meat products (e.g., cold cuts), meat-based dishes, omelets, and cheese dips — were in the fat/sodium cluster.

- 25% fell into the fat/sugars cluster, and these included sweets and desserts, but also foods such as glazed carrots and other vegetables cooked with fat and sugar.

- 16% were in the carbohydrate/sodium cluster, and these included items like pizza, breads, cereals, and snack foods.

We also looked at which of the USDA’s food categories contained the most hyperpalatable foods. More than 70% of processed meat products, egg-based products, and grain-based foods in the FNDDS met our criteria for hyperpalatability.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we found that nearly half (49%) of foods labeled as containing “reduced,” “low”, or zero levels of sugar, fat, salt and/or calories qualified as hyperpalatable.

Equally unsurprisingly, our definition covered more than 85% of foods labeled as fast or fried, as well as sweets and desserts.

Conversely, as one might expect, our definition of hyperpalatability did not apply to whole, fresh foods such as whole, raw, unprocessed fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, shellfish, whole grains, nuts, beans, or whole dairy foods (e.g., unsweetened yogurt).

A possible tool for tackling obesity

Our findings could be used in several ways, if research produces enough evidence linking foods meeting our definition of hyperpalatability to overeating, obesity, and adverse obesity-related health outcomes.

First, the FDA could require hyperpalatable foods to be labeled as such. That approach would alert consumers while preserving choice, but would likely meet with stiff resistance from food companies.

The agency also could regulate or limit specific combinations of ingredients to significantly reduce the availability of hyperpalatable foods, although that proposal would likely encounter even greater resistance.

Recent surveys show increased interest among U.S. consumers in making informed food choices, but they often aren’t sure which sources to trust.

Accordingly, our definition of hyperpalatability needs to be backed by more evidence before it is promoted as a tool for improving public health. But as a first step, people can try to avoid foods containing “addictive” combinations and levels of ingredients, such as lots of fat, sugars, refined starches, and/or sodium.

One starting point for people concerned about healthy eating is to base their diets on unprocessed or minimally processed whole foods with few or no added ingredients, such as fresh, unprocessed fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, beans meats, fish, shellfish, and whole dairy products.

As journalist and author Michael Pollan wrote in his book Food Rules, “Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food.”

Scientists identify brain circuits linked to impulsivity

By Craig Weatherby

A team of researchers from the University of Georgia and the University of Southern California have discovered a circuit in the brain that alters food impulsivity, creating the possibility scientists can someday develop therapies to address overeating (Noble EE et al. 2019).

“There’s underlying physiology in your brain that is regulating your capacity to say no (to impulsive eating),” said the study’s lead author, assistant professor Emily Noble in the UGA College of Family and Consumer Sciences.

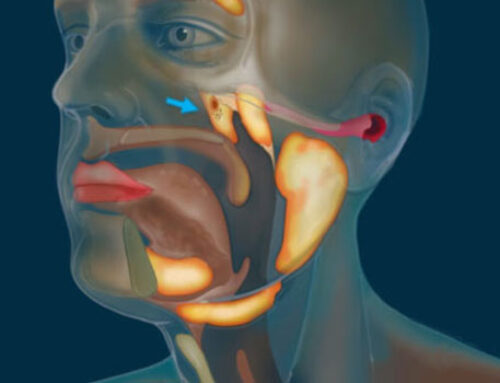

Using rats as their subjects, researchers focused on a subset of brain cells that produce a type of transmitter in the hypothalamus called melanin concentrating hormone (MCH).

Recent research in rodents conducted by European scientists showed that MCH stimulates appetite by interacting with an opioid receptor in the brain (Romero-Picó A et al. 2018).

According to Noble, while previous research has shown that elevating MCH levels in the brain can increase food intake, this study is the first to show that MCH also plays a role in impulsive behavior: “We found that when we activate the cells in the brain that produce MCH, animals become more impulsive in their behavior around food.”

To test impulsivity, researchers trained rats to press a lever to receive a “delicious, high-fat, high-sugar” pellet, but the rat had to wait 20 seconds between lever presses. If the rat pressed the lever too soon, it had to wait an additional 20 seconds.

Researchers then used advanced techniques to activate a specific MCH neural pathway from the hypothalamus to the hippocampus, a part of the brain involved with learning and memory function.

The results of the experiment indicated MCH doesn’t affect how much the animals liked the food or how hard they were willing to work for the food.

Instead, the circuit acted on the animals’ ability to stop themselves from trying to get the food.

“Activating this specific pathway of MCH neurons increased impulsive behavior without affecting normal eating for caloric need or motivation to consume delicious food,” Noble said.

As she said, “Understanding that this circuit, which selectively affects food impulsivity, exists opens the door to the possibility that one day we might be able to develop therapeutics for overeating that help people stick to a diet without reducing normal appetite or making delicious foods less delicious.”