Original article from SCIENCE

Ultrasound can reveal a leaking heart valve, expose a torn tendon, and give parents an early snapshot of their baby within the womb. Now, researchers have shown that ultrasound can also gauge whether certain genes are switched on in animals—a feat that could one day help researchers probe everything from tumor growth to the function of nerve cells.

“It could open up a whole new way of looking at the regulation of genes,” says biomedical physicist Michael Kolios of Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada, who wasn’t connected to the study.

Cells continually turn genes on and off. To illuminate that activity—or expression—in cells, researchers can genetically modify them so that when they fire up particular genes, they also produce glowing proteins such as green fluorescent protein (GFP). Although this approach works well for cells in culture dishes, the light from these proteins doesn’t travel far in the body, making it difficult to track gene activity inside tissues and organs.

Ultrasound, which produces images by bouncing high-frequency sound waves off structures in the body, could provide a solution, says chemical engineer Mikhail Shapiro of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. The noninvasive technique, he adds, is “really great” at peering deep into tissues.

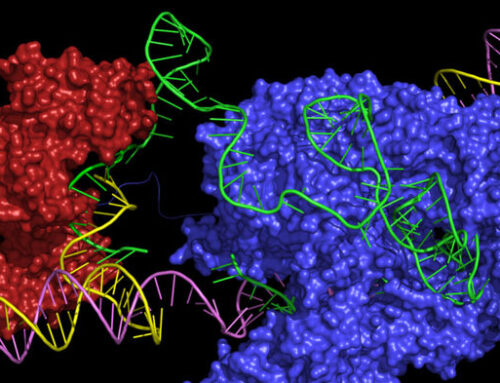

But individual cells are too small to distinguish with most ultrasound frequencies. That’s why Shapiro and his colleagues turned to aquatic bacteria that manufacture microscopic air bubbles that reflect sound waves. Inside the cells, the bubbles boost the number of sound waves that bounce back to the ultrasound device, making the host cells detectable.

Last year, a team that included Shapiro and Caltech bioengineer Arash Farhadi inserted 11 genes for producing the gas-filled spheres into gut bacteria and then injected the modified microbes into the intestines of mice. Using a small ultrasound probe, the scientists could pinpoint clusters of bacteria in the animals’ intestines.

Making the same technique work in mammal cells instead of bacteria proved trickier. Bacterial genes function differently from those of animals, and inserting so many bacterial genes into mammalian cells and getting them to work in concert is difficult. For instance, multiple bacterial genes often share a promoter, a DNA sequence that functions like an on switch, but each mammalian gene has its own. Farhadi, Shapiro, and colleagues discovered several workarounds. They found that by stitching several of the bacterial genes together with a protein from a virus, they could coax mammalian cells into activating the genes using one promoter. Inserting nine bacterial genes could induce human kidney cells in a dish to produce the gas spheres. Cells containing the capsules showed up under ultrasound, whereas controls cells didn’t, they report today in Science.

To test whether the cells are visible in an animal, the researchers transferred the genes into virally altered human kidney cells that they then injected into mice. These cells caused tumors to sprout in the rodents. When the researchers visualized the tumors with GFP, they appeared as green blobs. Ultrasound furnished a more precise image, showing that only cells at the rim of the tumors had turned on the bubble-producing genes. “You can see this beautiful expression pattern in the animals,” Farhadi says.

“It’s a neat acoustic way to probe the expression of genes in cells,” says radiation oncologist Gregory Czarnota of the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

But he and other scientists agree that researchers need to solve a few problems to make the technique widely useful. For example, the team’s genetic engineering approach is complex, says neuroscientist Sreekanth Chalasani of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California. “I would love to use this today,” he says. “If there was an easier way to put these genes in, I’d do it.”